Interview with Jerry Friedman

Jerry Friedman, entrance to Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico Photo: Natalie Khazaal

We live in a speciesist society that hangs on the cultural myth of human superiority rather than the fact of animal sentience. Sadly, science frequently fails to call attention to the myths and flaws that become commonly accepted as fact, and that, in turn, perpetuates our rationale for exploiting other animals. For example, it is commonly assumed that using other animals in research is of no consequence to them and of immense benefit to human health. On the contrary, vivisection inflicts horrific and unnecessary pain on other animals and in many instances is of dubious benefit to humans.

Facts about the composition of the food we eat (such as the calcium content in dairy foods, the protein content in animal flesh, or the Omega 3 fatty acids found in the bodies of fishes) have become misinterpreted as dietary recommendations. They have formed part of the cultural mythology that dictates who ends up on our dinner plate. These kinds of myth narrow the focus of our attention to animal foods, and obliterate the possibility of obtaining these same nutrients from plants. This leads to the ‘where do you get your protein?’ questions that vegans are often asked.

The research literature is replete with hypotheses and theories about human wellbeing. In contrast, theories and hypotheses on the wellbeing of other animals are either absent or present only to the extent that humans benefit when other animals are happy, healthy or well.

Myths and gaps in the literature point to the very serious issue of speciesism in scientific research. One of the scientific myths that is culturally unquestioned and that is used to justify human omnivorism, and our failure to even begin to think about animal equality at a societal level, is the notion that eating meat caused the human brain to evolve, somehow endowing the flesh of other animals with the capacity to confer intellectual benefits onto a single group of primates: humans. It is a myth that Jerry Friedman, American Lawyer and Animal Rights Activist, is thoroughly dismantling. Here he shares some of his ideas with the Friends of Eden in this issue of Somebodies, Not Somethings.

Jerry, thank you for talking to the Friends of Eden.

I will begin by asking you to outline the proponents of the theory that eating meat drove the evolution of the human brain and to briefly describe the evidence on which their theories are based.

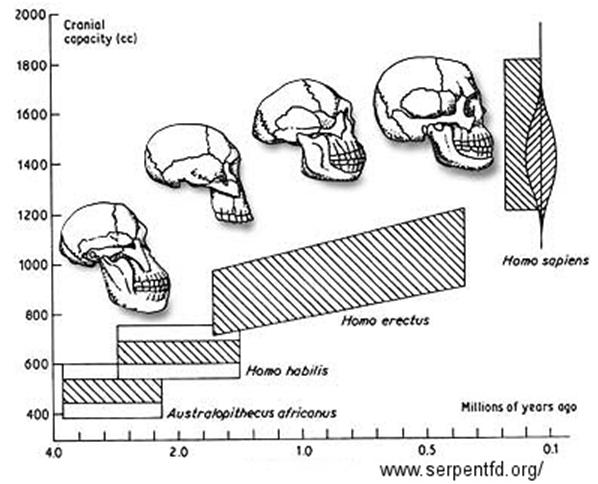

There are generally three hypotheses connecting hunting or eating meat with human encephalization—the evolutionary increase in brain size relative to body size. (1) “Man the Hunter” has been with us since the mid-20th century. It claims that the more intelligent pre-humans were better at hunting, and being better hunters they provided more food to their family. Thus the children of hunters were more likely to survive and reproduce. This created a positive-feedback loop of intelligent hunters that caused their brain to grow over hundreds and thousands of generations. The principal evidence that supports “Man the Hunter” is the once-believed correlation between human brain growth and development of stone tools and weapons. When this hypothesis was first developed, the periods of rapid brain growth seemed to match the periods of tool innovation, but later discoveries wrecked the correlation. For example, the earliest stone tools were dated ca. 2.2 million years ago, which was close enough to when Homo erectus, a large-brained ancestor, appeared ca. 1.8 million years ago. However, stone tools are now known to be used as early as 3.4 million years ago which is entirely too early for H. erectus. (2) The “Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis” was published in 1995 by Aiello and Wheeler, and it is the current front-runner hypothesis linking brain growth to hunting or eating meat. It uses a different correlation than “Man the Hunter.” All nonhuman apes have a similar brain-to-gut ratio, but the human brain is proportionately larger and their gut is proportionately smaller by the same amount. It appears that humans traded a smaller gut for a larger brain. The “Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis” argues that the only way our ancestors could get enough calories with a smaller gut was to eat more calories. Eating more vegetation would take too much time, so the authors conclude that our ancestors must have eaten meat for those calories. (3) A third hypothesis claims that meat has abundant micronutrients, particularly EFAs (essential fatty acids), and lots of EFAs are needed for human children while they undergo rapid brain growth from ages 1 to 5. Milton, the researcher, does not believe that plants available in Africa during the millions of years when our brain grew could have supplied enough EFAs, so the author concludes that humans needed to eat meat.

But you dispute these theories, and the evidence on which they are based, as myth, or cultural mythologies, that are used to justify meat eating. Can you tell me more about that?

Since before Aristotle, people believed that the universe was made for humans. In this case, Man the Hunter assumes that civilized humans evolved from so-called savage brutes in a way that places us above nature. There was no serious challenge to this anthropocentric and speciesist paradigm until Darwin published ‘On the Origin of Species.’ One reason why Darwin’s ideas were so controversial was because they challenged the belief that humans were somehow divine and above the animal kingdom. Darwin toppled the ideology of human supremacy, which was very difficult then and now for many people to accept. I believe Man the Hunter simply promotes and defends Man the Supreme, not based on science but based on the prejudices of 19th and early 20th century scientists.

As science became more sophisticated and anthropologists less colonial in the latter half of the 20th century, evidence of human origins came to be interpreted with less loyalty to an anthropocentric universe. Disciplines unavailable to pioneer anthropologists brought new evidence that were more convincing than stone tools charted against brain growth. For example, neuroscience showed that the areas of the human brain that grew the most were not related to hunting or eating meat, but to a wide array of social skills. Now it’s difficult to refute that our species’s social development was the primary cause of encephalization. We owe it to our ancestors’ evolving sense of community, critical thinking and problem solving, outwitting rivals and outsmarting predators, language, and development of fire and technology, for bestowing us with our large brain. There is no reason to give credit or special mention to hunting or eating meat.

Figure 1 Evolution in brain size (source https://frontiersofzoology.blogspot.ie/2011_09_01_archive.html)

What specific facts suggest that meat consumption does not account for the evolution of the human brain?

The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis is the leading hypothesis linking meat eating with our brain size, yet its authors write that, at best, they demonstrate only correlation, not causation. Without a mechanism explaining how meat causes brain growth, the Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis cannot be accepted as theory.

Correlation is an important scientific tool, yet correlation alone can easily mislead. Supporting evidence is extremely important for correlation to be adequate. While the Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis is well-reasoned and intuitive, its supporting evidence is equivocal. For example, recent research shows that a lot of our brain growth is due to fat which throws off some of the Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis’s calculations. Also, since our brain prefers calories from sugar (from plants) rather than fat (from meat), it’s counter-intuitive to suggest that our brain grew more fatty by eating meat.

Important correlations weren’t addressed in the Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis. A more inclusive analysis of correlations shows that hunting or eating meat has nothing to do with brain growth. (1) The most encephalized group of animals are primates, who predominately eat leaves and fruits. (2) Chimpanzees, who are the most persistent hunters and meat eaters among apes, have the same sized brain as closely-related bonobos who are meat-averse. (3) Predators, as a group, have a relatively small brain, including wolves who are known to be very clever. Even alligators use tools to catch prey, and their brain is remarkably small.

Figure 2 Crocodiles and alligators hunt using sticks to lure birds

Further, chimpanzees are terrific hunters with a brain much smaller than ours. If our close relatives can hunt well with a small brain, why would hunting or eating meat stimulate our brain to grow but not theirs? Man the Hunter advocates stumble to explain why they believe evolutionary forces acted one way on humans and a different way on all other animals.

Another important and unexplained issue is why the human brain has been shrinking for over the last 20,000 years. Full-scale hunting began around 50,000 years ago; agriculture began around 10,000 years ago; and in between these major events the human brain began to shrink. It has shrunk by about the size of a tennis ball. How could meat cause the human brain to grow for millions of years, but when meat is most available, the human brain shrinks?

What about other animals? How do their diets correlate with their brain size?

Animals are best compared with closely related species. We can’t compare the wings of bats with the wings of birds because they evolved flight under very different evolutionary pressures. In the same way, it’s most helpful to compare humans with apes and other primates if you want to make educated guesses about humans. Comparing us more distant mammals is less informative, and comparisons to birds, reptiles, and other non-mammals is strained.

With that in mind, apes and shrews are the only animal groups with an unusually large brain compared to their body size. Since all apes are predominately plant-eaters, clearly eating plants are sufficient for apes to evolve large brains.

Among apes, only chimpanzees are noteworthy hunters and their brain is the same size as their close-cousin bonobos who eat extremely little if any meat. Other close-cousin species show why meat is irrelevant to brain growth. Katharine Milton studied black-handed spider monkeys and howler monkeys, and discovered that the spider monkeys’ brain was twice the size of their cousin howler monkeys. Spider monkeys prefer to eat calorie-rich fruit while howler monkeys prefer calorie-poor leaves. Milton argues that the spider monkeys’ high-calorie diet combined with memory pressures to find seasonal fruit contributed to their larger brain size—so if meat was not necessary for other primates to double their brain size, why do some researchers argue that it was necessary for humans?

Among apes, only chimpanzees are noteworthy hunters and their brain is the same size as their close-cousin bonobos who eat extremely little if any meat. Other close-cousin species show why meat is irrelevant to brain growth. Katharine Milton studied black-handed spider monkeys and howler monkeys, and discovered that the spider monkeys’ brain was twice the size of their cousin howler monkeys. Spider monkeys prefer to eat calorie-rich fruit while howler monkeys prefer calorie-poor leaves. Milton argues that the spider monkeys’ high-calorie diet combined with memory pressures to find seasonal fruit contributed to their larger brain size—so if meat was not necessary for other primates to double their brain size, why do some researchers argue that it was necessary for humans?

We evolved from herbivorous beings, is that right? When did we become omnivorous and was meat ever more than a very irregular part of the human diet until we domesticated other animals?

Broadly speaking, humans evolved from florivores (plant eaters), but more specifically we evolved from and still are folio-frugivores (leaf and fruit eaters). I don’t use the term “herbivore” because herbs are a specific type of plant that, while humans eat herbs, they are an insignificant part of our evolutionary diet. An omnivore has no specialization, meaning that they eat plants and animals with equal ability. Anatomically humans are poor meat eaters. Hunting animals without technology is a gamble we usually lose so society turned to growing them in cages, now called factory farms. Unlike true predators, we need tools to kill and render them, we must cook them for several reasons, and while we can digest meat fairly well, meat in our diet promotes several degenerative diseases. Our anatomy makes it clear that we specialize in eating plants, so we cannot be omnivores.

The earliest evidence of human ancestors eating meat comes from ca. 3.4 million years ago but there is no evidence of our ancestors’ total diet. Because our ancestors that far back were quite small and had no anatomy for hunting (no claws), they must have had a plant diet. The tools show they were infrequent scavengers.

The earliest spears are dated to ca. 500,000 years ago. Experts generally agree that our ancestors began regular hunting of large animals around 50,000 years ago, hunting fish around 14,000 years ago, and agriculture around 10,000 years ago. Meat has only been a regular part of the human diet for the last 50,000 years. In the last 100,000 years, there is no evidence that our anatomy evolved (although some humans evolved more tolerance for milk in adulthood), so there is no reason to believe that humans have evolved at all toward eating meat. Humans and other plant-eating mammals can digest meat thanks to our insect-eating ancestors from 60 million years ago—we have not been evolving toward eating meat, we have been evolving away from it.

What other evidence suggests that humans evolved as folio-frugivores and not omnivores.

The best evidence for our ideal diet is to identify what kills us. Humans who eat more plants live longer and suffer from fewer diseases. Humans who eat more animals, including milk and eggs, tend to die younger and suffer from more diseases.

Beyond medical studies, human attributes like rich color vision (to find fruit), agile hands (to climb branches to reach and grab fruit), pre-molar teeth (that excel at tearing leaves and scooping fruit), cusped molars (that excel at crushing cell walls, found only in plants), a slow-moving digestive tract while carnivores of all sizes have a fast moving digestive tract, and countless other attributes show humans were designed by evolution to eat plants.

If the term “omnivore” means an ability to eat plants and animals, then almost all animals are omnivores: lions eat grass for vitamin B9 and other plants, chimpanzees eat termites for vitamin B12 and other meat. Even some cows are fed meat by humans so they are omnivores by this definition, but no one thinks of lions or cows as omnivores. Nor should anyone think of humans as omnivores simply because we have the capacity to eat plants and meat. We get the same confusing results if “omnivore” means what one chooses to eat—Florence is a captive nurse shark who chooses to eat vegetables. She is not a florivore or omnivore, she is a pescivore (fish eater) who chooses to eat plants. The trend now for dietary labels is to describe the animal’s specialization. This gives us intuitive and informative results: lions are carnivores because they specialize at eating mammals, cows are graminivores because they specialize at eating grass, and humans are folio-frugivores because we specialize at eating leaves and fruits. Omnivores have no specialty—rats, crows, ants, and a few other animals can secure and digest a broad range of food with no particular advantage.

Of course the question is hypothetical: even if we have the capacity to survive on or even thrive on an omnivorous diet, the fact is that it is not necessary for human health or wellbeing and it causes harm to the animals we use for food, and thus we have an ethical obligation to eat as if we are plant eaters. Do you believe that if the dismantling of this myth were to become more widely accepted that it would help the plant based diet become more accepted and thus help the non-violent philosophy of veganism become more mainstream?

All members of the human species fare better when myths are dismantled. Dismantling this particular myth, that we should or must eat meat for any reason, will benefit all animals. Humans benefit morally by reducing suffering, physically with improved health, and economically with a wiser use of resources. Nonhumans benefit by living as they want to: not to be born into a life of misery, then murdered shortly thereafter.

You suggest that the ‘Man the Hunter’ hypothesis that suggests that the most successful human hunters were intelligent enough to catch other animals, and that because they had enough to eat and to feed their families, their genes, and hence their intelligent hunting capacities, survived and thrived, is yet another myth. Can you tell me a little more about your views on this and why you regard it as further mythology?

There are several problems with this tale because, while early evidence supported it, discoveries since the 1980s increasingly refute it. The physical evidence—fossils, tools, etc.—reveal humans as prey animals before ca. 2 million years ago, long after the human brain started its upward turn. These early ancestors were too vulnerable to be hunters. Later humans, particularly H. erectus, hunted but there is no evidence to support when they started hunting nor how much meat they ate. Remember, H. erectus arrived ca. 1.8 million years ago but the earliest evidence of spears are dated to 500,000 years ago. We can fill in the gaps with convenient ideas, such as spears or other hunting weapons being developed 1.6 million years ago, but there is no supporting evidence. However, there is abundant evidence that human ancestors ate mostly plants, some insects, and rarely a lizard or bird, for the last 60 million years. Our anatomy shows humans have never been deft hunters. Our physiology shows meat has never been an important part of the human diet. Using the last 50,000 years as a model for the last 60 million is ideological and not scientific.

So, you are clarifying the simple point that although there is a correlation between hunting and meat eating and the evolution of the human brain, the association is merely correlational and it tells us nothing concrete about the causal factors in human brain evolution. Furthermore, you call attention to the dearth of evidence in the literature demonstrating meat eating as a causal factor in human brain evolution. Has anyone been able to provide convincing evidence that meat eating was anything other than a correlation of the increase in the human brain in evolution?

Every hypothesis that links humans eating meat with an increase in human brain size has either been refuted or the supporting evidence doesn’t support it well. The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis works equally well with our ancestors eating meat or cooked vegetation, and because cooked vegetation would have been easier and safer to get and there is no reason to believe our ancestors could have secured much meat, cooked vegetation is the more reasonable answer. Milton claims that meat was critical for our ancestors because EFAs found in meat are especially important to human children. She does not consider the EFAs found in tiger nuts, which were and are abundant in Africa, nor does she consider the likelihood of our ancestors eating plants along lakes and rivers that would have been covered in algae, another rich source of EFAs. While our ancestors surely ate some meat, and got some EFAs from meat, it’s hasty to conclude our ancestors needed meat for nutrients found abundantly in plants. These researchers give unearned credit to eating meat.

Figure 4 Chimpanzee mother and child

Figure 5 Bonobo mother and child

So, what was responsible for the evolution of the human brain? Processes of socialisation? Can you elaborate on that?

The best way to explain how and why organs evolved is to look at what function they serve. The areas of the human brain that grew the most since we split from our last common ancestors with chimpanzees relate to problem solving, sensory perception, planning and awareness of time, language, and a more sophisticated understanding of the world. These skills can all be used for socializing, and they enabled our ancestors and ourselves to build community far beyond the communities of other primates, especially with our mastery of language. While language would help our ancestors coordinate a hunt, language helps in many more ways. Here again, researchers who argue that hunting stimulated language and a larger brain give unearned credit to hunting.

You mention the concept of evolutionary commitment. What do you think are the consequences of the human abandonment of our evolutionary dedication to eating a plant only diet?

Evolutionary commitment merely states that the more an organism is invested in a certain way of living, the less likely the organism will switch to a different way. Birds, for example, have so many biological processes dedicated to laying eggs that it would take enormous evolutionary pressure over a very long time for them to switch to live births. In the same way, our ancestors have been folio-frugivores for at least 60 million years. There is no reason, and no evidence, to believe that humans are losing our plant-eating specialty, that is, becoming more omnivorous. The consequences of humans behaving more omnivorously are seen in disease statistics and climate change.

Of all the facts you have garnered that dispute the myth of the meat eating:human brain evolution correlation, which do you think is the strongest?

If I had to choose one fact, I’d point to our close relatives, the chimpanzees and bonobos. Why their brain is the same size despite chimpanzees hunting and eating meat shows that neither activity causes encephalization. If evolutionary forces act equally, chimpanzees should have a larger brain than bonobos. Hence something else had to cause our brain to grow. Fortunately, I don’t need to choose one fact. If someone is not convinced about chimpanzees and bonobos, there are many more facts to choose, like the spider monkey who doubled their brain size by eating fruit, being active and social, and possibly exercising their memory.

Can you talk about what might be causing the current shrinking of the human brain and what, if any, are the implications of this change in human brain size?

I have read little research on this. My personal hypothesis includes two components. First, the human brain is very sensitive to temperature so its size is controlled by its ability to stay warm and cool (thermoregulation). Colder climates should pressure the brain to grow so it can keep warmer, and this is seen with the Neanderthals in Europe who had a very large brain. Anatomically modern humans who evolved in Europe also had a larger brain than humans today. Then, as the planet warmed, their brain was pressured to shrink to keep cool.

Evolution favors energy efficiency and brain tissue uses a lot of energy, so evolution should pressure all animals’ brains to be as small as they can be unless food is plentiful, or unless a larger size confers an advantage. If the human brain reached its peak performance 20,000 years ago, it follows that later humans with smaller but equally effective brains would be favored by evolution. Gradually, the human brain would shrink to a size that offers peak performance with minimal energy use.

As long as food is plentiful, there shouldn’t be any pressure for our brain to shrink further, nor is there pressure for it to grow unless larger size again makes a difference. Since we now store knowledge outside the brain in books and computers, I don’t foresee any pressure for our brain to grow.

Who are the scientists who support your hypothesis? On what evidence are they predicating their theories of human brain development?

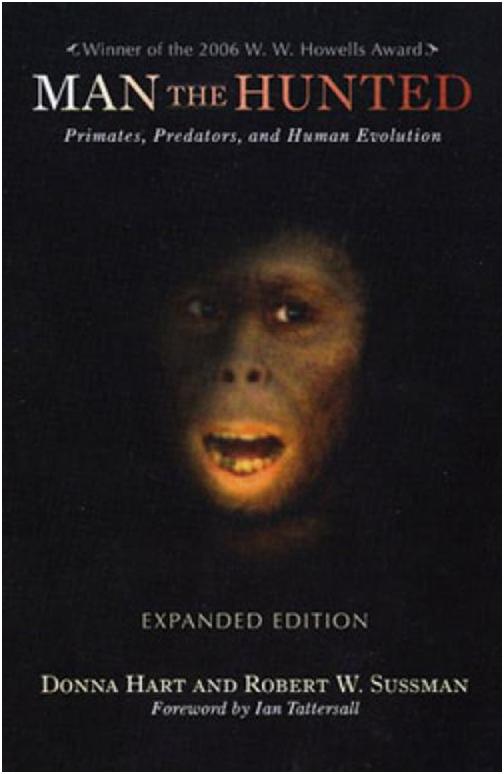

Scientists who argue against meat being necessary for human brain growth include Richard Wrangham (“Catching Fire”), Donna Hart and Robert Sussman (“Man the Hunted”), Dean Falk (“Braindance”), among others. Some take a moderate view, like Peter Ungar who argues that our ancestors survived with a flexible diet and no single food source should be emphasized. Generally, they claim that other evolutionary forces explain brain growth better than hunting or eating meat: cooking and socializing, evading predators and socializing, and improved thermodynamics and socializing respectively. I defer you to their books to understand their specific criticisms.

Of course, even if you were wrong; even if eating meat was the essential causal factor in human brain development, the ethical argument that we are not entitled to harm others for our own progression still stands. But your scope is broader, isn’t it? Your scope is identification of speciesism in scientific research. What are the most significant examples of speciesism that you have discovered in your research?

The most profound example comes from Descartes and his present-day followers who believe that nonhuman animals cannot suffer, or that their suffering does not matter. Vivisectors, who perform physical and emotional experiments on nonhuman animals, who would not perform the same experiments on human animals, are speciesist. The term “speciesism” is parallel to racism, sexism, and similar words that amount to an arbitrary oppression of other classes of beings. Darwin proved that humans are one type of animal, and his argument provides the framework that all animals have the capacity to suffer. Our lay observations and scientific research confirm it, but vivisectors use nonhumans as though they were the unfeeling machines that Descartes believed them to be.

What other examples are there of speciesism in scientific research that support cultural myths that enable humans to continue exploiting other animals?

I am amazed at how many medical professionals, from doctors and surgeons to dieticians and nutritionists, push a meat-based diet. Those I’ve asked tend to claim that meat doesn’t do much harm, or their patients would not switch to healthier Vegetable Diet fare even if directed to. One physician told me that his heart attack patients, after waking from emergency surgery, often asked for pork chops. I believe that medical professionals and their patients are bound together in these cultural myths, that humans evolved in-part to eat animals, or that we owe our large brain to eating animals so we should continue. The irony here is how our large brain has made so many people choosing disease-promoting culture rather than health-promoting reason.

We all have a tendency, don’t we, to look for evidence that supports our deeply held beliefs? But scientists tend to think of themselves as being able to remain objective and remain impartial to the influence of personal beliefs or inherited cultural mythologies. So, in the interests of scientific objectivity isn’t it incumbent upon scientists to take note of your research and identify their own researcher reflexivity? After all, our education and training as scientists takes place in a speciesist culture; that must affect how we work and what we test. Moreover, our scientific education and training takes place in a speciesist culture that inflicts great harm and suffering on other animals, on the environment, on human health, and on the humans employed in animal agriculture and research. One would imagine that these facts are sufficient rationale for scientific examination of our own speciesism and in order to overcome the influence of our embededness in a speciesist world. Has there been much scientific interest in your theories from outside the animal rights movement?

Clearly, the human experience ties us to our past, our heritage, and our culture. Society looks to scientists to move civilization away from our superstitions, but some scientists are superstitious such as those who believe humans are destined, by evolution or divine mandate, to conquer nature.

I would like to see more skepticism in science. This is a slow process, but occasionally I see change for the better. After an international body of scientists argued that dolphins should be considered nonhuman persons, India declared them so and now India is closing its dolphin prisons. Neil deGrasse Tyson, an astrophysicist and educator, has emphasized that humans are not the pinnacle of evolution and all animals deserve respect.

I have presented my research to people in and out of the animal rights movement. All of the feedback I’ve received, whether from anthropologists, professors, and other academics, as well as the general public, has been positive albeit in varying degrees. While it doesn’t prove anything, I especially appreciated a skeptic who told me before my presentation that he would not change his mind unless he was convinced “beyond a reasonable doubt,” which is a very high standard. After my presentation, he said that I was persuasive, and that he is rethinking his relationship with the rest of the animal kingdom.

The influence of speciesism does not make for accurate science, does it? By way of illustration, can you elaborate on the attribution of protein in Neanderthal bone analysis to meat consumption when the source of that protein is just as likely to have been plant food?

As I’ve said, our past affects our perceptions. Ever since Neanderthals were identified as a different species (they were previously thought to be diseased or deformed modern humans), society imagined Neanderthals as a splinter species stuck in the savage life of hunting. Around year 2000, studies conducted on Neanderthal bones revealed a very high amount of protein that fit into the assumption of Neanderthals as savage hunters who ate very little if any vegetation. Then, in 2010 and 2012, Neanderthal dental plaque was studied. It revealed an abundance of seeds and other plant matter, and very few lipids (animal fat). The researchers admitted that they wrongfully assumed high protein in the bones meant high meat in the diet. Now, no one is certain what proportion of food Neanderthals ate, but we know they ate plenty of veggies.

Other studies follow the same mistakes. One researcher, Neil Mann, claims that because one set of australopithecine (a human ancestor species) bones has high grass-carbon content but their teeth show no indication of grass abrasion, they must have gotten the grass-carbon indirectly from eating grazing mammals. This researcher uses one chemical study for his grand conclusion which is again a perilous method of analysis. He does not consider other sources of grass-carbon like tiger nuts that would not be abrasive, and amusingly he works on behalf of the meat industry. No bias there.

You are a lawyer. How did you become interested in animal rights and the scientific study of other animals?

I went to pre-veterinary school for an undergraduate degree in biology. The school, New Mexico State University, only taught how to make nonhuman animals healthy enough for slaughter, which was not why I wanted to become a veterinarian. The school’s anti-animal program and cruelties I witnessed there wrecked my morale. I dropped out of NMSU after a few years and changed my life’s direction to help nonhumans systemically rather than individually. That eventually led me to becoming an attorney, especially to help defend animal advocates when they are arrested or sued for free speech. I’ve maintained my interest in science all along, especially human evolution.

Has your research been published?

This research has not been published. I expect to submit it for publication this summer.

Jerry, thank you very much for taking the time to do this interview for Somebodies, Not Somethings. I, and the Friends of Eden, will watch the progress of your research with great interest.

You can learn more about Jerry’s work can be found at the following sites:

Go Vegan Radio interview: https://www.goveganradio.com/2014/03/05/02-march-2014/

Houston Oasis presentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCbPDld4-l0